Last weekend, the Portland Thorns pulled off incredible victories on several fronts. They won the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) championship, besting the Kansas City Currant 2-0 in an exciting, nationally broadcast final. They did so after a devastating cascade of events and revelations related to a history of abusive coaching, and amidst major questions about how such abuse was allowed to run rampant across the league.

In this, the 50 year anniversary of Title IX, all of these things are amazing for different reasons. And they all weave together in a tapestry that demonstrates the complexity of what organizational trauma often looks like: a giant, chaotic mess that’s nearly impossible to effectively describe. Trauma is typically described as an experience that leads to distress, whether physical, emotional or psychological. It is always a deeply personal experience, but trauma can also apply across an organization—particularly when people in power misuse that power to control others. Just as people must work through a healing process in order to recover from trauma, so must organizations.

A Case Study of the All Too Common

In the case of the NWSL, widespread, persistent abuse reported over the last several years was finally confirmed by an independent investigation that concluded in September. The findings were nauseating. Not only did the investigation reach scathing conclusions about widespread and ongoing abuses, but it also quickly became evident from further reports that it merely scratched the surface of abuse that has marked the NWSL and its predecessor organizations. Worse still, it implicated the feeder clubs serving even more vulnerable teenage girls. Possibly worst of all, the report found that the abuse continued, as an open secret in the league, well into 2021. Well past 2017, when the already 11-year-old Me Too movement exploded. Well into decades of consistent success by the U.S. Women’s National Team in almost every major contest on the world stage. How could this be?

Unlike Major League Soccer (MLS), the male counterpart to the NWSL, which launched in 1996, the NWSL is only a decade old and has struggled since its inception to gain the following, funding, and coverage of its men’s counterpart. To say the league’s existence is tenuous would be understating its financial reality (at least until 2020), and with only 12 teams (compared to MLS’s 29), spots for pro women players are few and far between even for the very best players in the world. In short, the abuses detailed in both the investigatory report and by many brave players since really could crater the organization or any one of its teams—making the precise reason that so many people failed to address patterns of abuse in the first place become the league’s reality.

If that seems maddening, consider that, even if the NWSL withstands this enormous reputational blow, the long-term effects of broken trust and a fear-based culture could push the same consequences down the road with the added benefit of a few painful years of limping along in between.

An organization doesn’t have to experience blatant abuse to fall into such a trap, and many with just one unchecked toxic leader are at risk of falling into the abyss of eroding trust. Sadly, simply expelling such people, while necessary, is never enough. The future, however, is not an inherent disaster. The Portland Thorns are already becoming an example of a recovery story. In a moment when they could have been torn apart by a painful legacy, they instead pulled together and established themselves as a true team. Some credit this success in part to Head Coach Rhian Wilkinson, yet even with great leadership, recovery requires a group effort.

Recovering from Trauma within the Organization

In our work with organizations that have experienced a collective trauma, whether it be at the hands of a particular individual or group of leaders, or by the ways that people in power neglect their responsibilities to establish and maintain a healthy culture, we always begin with the same work: trust. (Yes, I know that trust has recently become a popular term that people throw around like everyone knows what it means and how to create it. Don’t worry; we feel that disconcertion, too.)

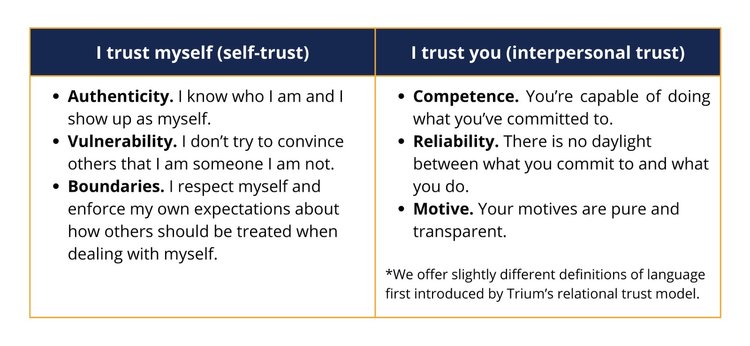

For most people, trust is a “know it when you don’t have it” experience and that means specifically defining trust in order to build or repair it is theoretically possible but practically out of reach. We’ve tried to help address this theory-practice divide with a few practical principles: (1) you must trust yourself before you can enjoy true trust with others and, (2) you must understand what you expect of others and what others expect of you to form and maintain trusting relationships. Each of these ideas can be broken down into three elements (see below).

Based upon Outside Angle’s experience helping to repair broken organizational cultures, I’ll offer a few ideas for ways that the NWSL and its teams might begin to repair the broken trust among its team members, staff and players as well as owners, investors, and fans.

-

Act immediately, and leverage recent transparency to set a new standard for naming problems.

Right now, emotions are raw but the hard work of telling the truth is done. It’s easy to conflate this with the end of the change process. In fact, it’s merely the beginning and shifting away from the old ways of operating requires attention and energy every day.

-

Develop a shared accountability strategy for ensuring that old habits are truly dead.

The vision for the future is clear: an organization where people are safe and supported as they pursue excellence in their craft. Now it’s up to leaders to work with their teams to define the process for ensuring that vision becomes reality. How will individuals work together to ensure something like this never happens again?

-

Encourage and proactively offer support for reflection and self-trust repair.

Authenticity, vulnerability, and boundary-setting sometimes require therapeutic support, but they can all be reinforced with organizational strategies as well. Encouraging people to be clear about who they are and what they stand for, and acknowledging that no one is required to be perfect, to conform to standards that are irrelevant to their work, or to do things they’re truly not comfortable with will only help improve their ability to show up and get work done.

-

Develop a lightweight shared progress monitoring cycle that ensures ongoing progress.

Not all of the work that people do to develop trust can be managed from an organizational level, but those things that can be managed must be clearly defined and measured. Without such a process in place, improvement might happen, but it will be difficult to know whether enough improvement has happened. Find the biggest levers and focus on 3-5 that are measurable.

Signs are positive that the NWSL’s future is not an inevitable failure, but without an intentional approach to repair and development of more productive organizational habits, it’s still in danger of falling back into the same old problems. Your organization may not be rocked by such severe abuses, but threats to trust require the same intention and ongoing attention for true cultural repair.

Check out my next post in this two-part series on responding to and recovering from organizational trauma. I dig in to the topic of interpersonal trust (also referred to as relational trust), what it is, and how it comes into play when there’s been a breakdown amongst members of the team.