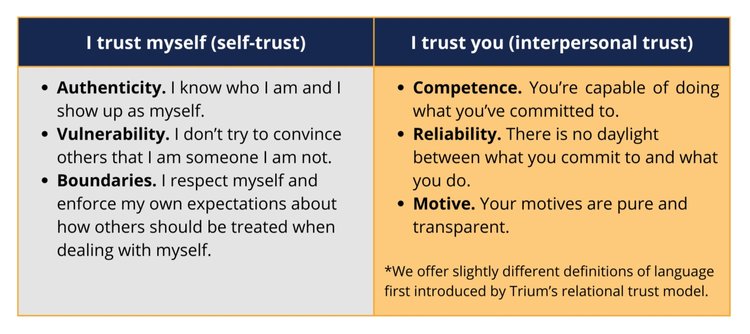

A couple weeks ago, I wrote about the National Women’s Soccer League’s (NWSL) heroic efforts to unpack years of abuse and mismanagement and chart a productive course forward. I suggested that even in a world where women’s professional sporting events are enjoying their largest viewership ever, the relationship between teams, leagues, and fans is still tenuous—and failure to repair and establish a solid organizational foundation could put the NWSL on the same path as its two failed predecessors. Mirroring the way our team at Outside Angle supports organizations in these instances, I framed my suggestions for recovering from trauma in two parts: beginning first with self trust and then working to rebuild interpersonal trust.

Interpersonal Trust In Action

The structure of the relationship between the NWSL and the U.S. Women’s National Team (USWNT), in combination with the challenges both sets of organizations have faced over the last decades, offers a remarkably strong analogy for so many of the companies and organizations we support. (And I also love soccer. Win-win.) Over the summer and early fall, players from across the NWSL’s 12 teams play against each other while concurrently competing for positions on the unified USWNT, and then competing together on an ever-evolving USWNT roster. The result is that players must learn how to both collaborate with and compete against each other, making strategic choices about which to prioritize at any given time. It’s also true that some teams across the league are better-resourced than others, and that not every player has equal access to great coaching, care, etc.

In other words, it’s a lot like working in many organizations. If ever there were a time when interpersonal trust were more important than the transition points among discrete teams, it’s hard to identify what they may be.

Competence

First things first, the people on the team with you—whether your home team or the ultra elite National team—must be qualified for and able to very effectively and consistently execute their jobs. Competence is about showing real skill and ability to apply that skill in the right way at the right time. If your skill is in question, it’s hard to rely on you to help get the job done.

In soccer, without competence no one will pass you the ball. Other team’s defenders will leave you alone, and gang up on someone else. This could happen because your foundational ball skills are poor—you struggle to pass, turn, or transition—or because you’re quite skilled when it comes to the fundamental moves but overly focused on winning your own shots. You shoot when you should pass. You miss opportunities to run interference because you’re only focused on your own position. In the workplace, this can look like “incompetence” that comes in the form of consistently missing the bar, doing the wrong work, making poor calls, or generally failing to understand the work. It can also look like forcing your way of doing things on colleagues, taking opportunities for yourself that could be shared or taught to newer staff, or making choices that have unnecessary negative consequences for others.

Reliability

It’s not enough to have the skills you need to get the right work done at the right time. It’s also important to be reliable—to execute consistently and with quality. If you make great decisions only one in every three times you get the ball, it will be difficult to choose you for the next big play. If you can play well, but only for the first 15 minutes, you won’t make the roster. Reliability isn’t about being perfect all the time, but it is about consistency. In the workplace, that means you do what you say you’re going to do every time. You miss the bar rarely, and when you do you acknowledge it and make corrections accordingly. If you’re reliable, you will sign up to do the work that needs to be done without regard to whether you really enjoy it, knowing that it is the next right thing to do.

Motive

Finally, interpersonal trust requires a clear and transparent motive. If you set others up for shots that you know they cannot make, you not only undermine their opportunity to be successful, you also undermine the team’s efficacy and reduce the likelihood that they’ll set you up for success down the road. Sometimes the right decision is a seemingly selfish one—you decide to go ahead and take the shot rather than passing, or you go ahead and do the work rather than collaborating or teaching someone else to do it. It’s right because, in your best judgment, it is the most efficient, effective and accretive thing to do. You make that clear by either nailing the shot or by showing through the product that you did your best. And even if you miss the shot or make the wrong call, your approach to explaining your decision is honest and open rather than defensive or concealed.

Building and Repairing Interpersonal Trust

All of these concepts may seem perfectly reasonable, but not at all actionable if you’re trying to establish new relationships or repair damaged ones. That’s exactly why we spend so much time getting clear about what these look like, and unpacking the ways in which they are either reinforced or violated within an organization. To be clear, building and repairing take time, and often an excruciating amount of time. It’s nevertheless possible to repair broken trust and to build the kind of bulletproof trust that can transcend the inevitable ups and downs of an organization’s life cycle.

There are three things that we’ve found to be successful in our work with organizations working to improve trust among team members. If you’ve diagnosed that interpersonal trust may be an issue inside your organization or team, consider taking these steps.

-

Build the honesty muscle.

For the most part, people don’t like to give critical feedback. Even when they’re incensed, even when they will directly and candidly explain their concerns with everyone else, they struggle to confront challenging issues with the people whose behavior must change. Leaders can establish a norm around direct and explicit (but not cruel) feedback early to help make sure this muscle develops. For those repairing after a problem, it is imperative that every leader creates space and demonstrates empathy (not judgment or retribution) for those who speak up.

-

Don’t wallow.

Creating space and listening will take time. Finding the right response will take time. These things should not be rushed. But it is equally problematic to give so much airtime to the problem that no other progress can be made, and everyone descends into a shared misery. Listen. Make sure you understand. Then lay out action and hold yourself publicly accountable for it. Do the same for others whose behavior must change. Take the first step in burying the hatchet. Don’t continuously punish people for old crimes. That doesn’t mean everyone must proffer forgiveness, or that people who must change are off the hook. It does mean acknowledging that people are better than their worst behavior.

-

Develop shared vigilance.

All leaders, but especially the chief executive are charged with being guardians of organizational culture. That means establishing conditions where those who violate cultural norms and expectations stick out like a sore thumb. Trust usually deteriorates behind the scenes. People should be explicitly aware of what culture norms are and be able to communicate their experience when they feel something is off. That can look different depending on the organization, but examples include leaders specifically checking in with their teams about culture and engagement and establishing anonymous reporting opportunities.

While I wouldn’t wish the abuse and mistreatment that for too long characterized women’s professional soccer in the United States, their experience also presents an example or value: the Yates report dropped just as the end of season playoffs were heating up, and the USWNT faced a slate of friendly games with their most talented European rivals, England and Spain. In short: they could not stop to feel sorry for themselves, even as they were digesting a disturbing reality. Results help demonstrate what a repair in progress looks like.

While the embattled Portland Thorns pulled together to win the league championship, the USWNT struggled through losses to England, Spain, and Germany in quick succession. Watching those games was painful, not because they lost, but because they so frequently missed out on opportunities to make plays together. Opportunities for shots on goal weren’t hard to come by, but the coordination to get the ball into the net was weak.

After watching the team struggle through a spate of losses, fans and pundits wondered whether the USWNT had lost its mojo. But head coach Vlatko Andonovski reassured that the team was resolute and that bringing the team together takes time and patience. The next day, the team scored two successive goals made possible by coordinated efforts that both emerged from the U.S.’s goalkeeper aggressively recovering the ball and getting it down the field for a series of passes that made it possible for two of the team’s newest players to score. In other words, they scored when they succeeded in working together. It certainly wasn’t a perfect game, but the spark of trust, and its impact, is evident.